|

|

:: [ A brief History of Andre Citroen and of the 5CV Citroen Model C ]

::

(Written

in 2001)

Part 1/. Brief History of

Bozi Mohacek's 1921 Citroen 5CV " L'Escargot "

Part 2/. Andre Citroen and his introduction to double chevron gears.

Part 3/. Andre Citroen and his connection with Mors and Munitions

Part 4/. Formation of the 'S.A. Andre Citroen' Car Company.

Part 5/. Brief History of the Model C 5CV Citroen

Part 3/. Andre Citroen and his connection

with Mors and Munitions

In 1908 Mors were in trouble. Emile and Louis Mors had commenced

manufacture of quality cars in 1895 and quickly established an enviable

racing reputation having vanquished the reigning Panhards by 1899. Mors

was a very innovative company and sales grew quickly fuelled by their

continuing racing successes including wins in the Gordon Bennetts of

1904 and 1905. However by 1908, the Depression had set in in France and

sales of Mors cars, which were generally large and expensive, dropped

dramatically. Mors withdrew from racing and even though the demand for

Mors cars was still there, production dropped to a low of 10 cars a

month.

In view of Andre Citroen's reputation for technical expertise in

mass production, Mors President Harbleisher invited Citroen to join Mors

and try to turn the company around. Citroen took leave of absence from

his gear business and brought with him Georges Haardt from the gear

factory. The Citroen style of management and production quickly began to

improve Mors' performance and he succeeded in reaching production of

2000 cars by the end of 1909. By 1913 the production was up to a level

of 100 cars per month and the Mors future seemed assured.

In the meantime Citroen's gear business was doing well in his absence

and, as his work at Mors was done, he returned to running his own

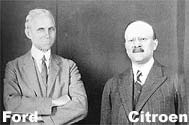

company. During the previous year, while still at Mors, he had been to

the USA and had inspected the Ford River Rouge plant in Detroit. Unlike

Mors where various departments were on different floors, the Ford plant

was all on one level with plenty of space and light. This convinced him

even more on the benefits of fluid mass production and he decided to expand

production at his gear factory even more. To finance the expansion he

went public in floating 'Societe des Engrenages A. Citroen'.

In the following year, 1914, the war began and Andre Citroen, who was a

captain in the Army Reserves, returned to the Army as a member of an

artillery regiment with 75 mm field guns. Early on, the regiment got a

pounding to which they could not respond due to a shortage of

ammunition. Citroen immediately spotted that here was a requirement and

an opportunity to mass produce shells in the same way as he had done

with gears. He quickly prepared a business plan which he submitted via

an old school friend Louis Loucheur, to the Minister for Armaments

Albert Thomas, who rapidly passed it on to the Army's Chief of

Artillery, General Baquet. The plan was accepted immediately.

The Ministry of Armaments swiftly supplied Citroen with funds to

purchase thirty acres of ground on the Quai de Javel in Paris on which in 1915

was rapidly constructed a massive lightweight factory complex.

The Ministry funds also covered the purchase all the requisite new

machinery from North America needed to produce 20,000 shells per day.

The Quai de Javel complex was massive, impressive, containing everything from

production lines to shops, 'cantine electrique', medical and dental

clinics, toilets, cloakrooms and all other facilities for employing more

than 12,000 workers.

Citroen was keen on worker benefits which not only

made him popular but also ensured stable production. As the war was well

under way and men were in trenches, the works were staffed mainly by

women, 'munitionettes', and Citroen paid special attention to a support

system for women covering pregnancy, birth, and paid leave

while nursing. By the height of the war, the Quay de Javel factory was

turning out more than 35,000 shells every day, and, in order to

integrate national ammunition production, other ammunition factories

producing a further 20,000 shells per day were placed under Citroen's

control; 55,000 shells per day. It was during this period that Citroen's

welfare interests were further nationally recognised in the introduction

of the concept of food rationing cards.

As the war drew to a close and the requirement for munitions started to

decline, Citroen began to look at other ways of utilising a fully

equipped precision manufacturing plant with enormous production

capacity. While it was probably inevitable that Andre Citroen would

remain within the automobile industry, he was not looking at the

automobile as a piece of artistic design nor a suitable means of

transport, but as a product with a mass market potential. Had there been

some other item which had more marketing potential and which could have

been built in his factory, then the Citroen Car might never have existed.

As it

was, the diminishing time frame, his previous experience at Mors and

meeting with Henry Ford led him in the direction of investigating

manufacture of automobiles. Citroen was not a designer nor knew much

about the workings of a car. For this he would need others. His was to

provide the concept, the production and the marketing.

It was as early as 1917 that Andre Citroen put out feelers as to who

could provide the designs for his car. The first to offer their services

were Artauld and Dufresne, who were working for Panhard and who provided

a design for a four-cylinder 3-litre 16 hp car. Citroen built three

prototypes which underwent extensive testing. It seems however that he

was not convinced by the size of the car, anticipating that mass

production would be better suited to a smaller more economical vehicle

which would appeal to the increasingly wealthy middle class. The

prototypes were sold to Gabriel Voisin who developed them further as his own.

Continue

with Part 4/.

(Written

in 2001)

Copyright © MMI, Bozi Mohacek. Reproduction only

by permission from the Author.

Go

to Recent Venues Page

|